24 October 1812 marks the Battle of Maloyaroslavets in Napoléon Bonaparte’s Russian Invasion when Field Marshal Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov’s 80,000 Russian infantry, 10,000 Russian and Cossack cavalry, and 600 guns fought Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte’s 60,000 French, German, Italian, and Polish infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 360 guns in a decisive battle that doomed the Grand Army to starvation and destruction.

On 19 October, Napoléon began the long retreat from Moscow. Despite considerable training and experience, his men were in a poor state. Supplies were low. Indeed, many men discarded them in favor of plunder. Horses were malnourished and exhausted. This impeded the artillery’s ability to move and deploy quickly. Cavalrymen were so poorly mounted as to nullify their scouting and charging abilities. Men and gunners had ammunition for only one great battle. Morale and discipline were at an all-time low. In letter after letter, soldiers expressed despair, homesickness, and certainty that Russia would be their death.

Knowing this, Napoléon hoped to avoid battle. He needed to reach Smolensk and Vitebsk before winter set in. There were two routes to choose. An army marches on its stomach. The French were experts at living off the land. But a large army strips a land bare quickly. Napoléon had come to Moscow by way of Mozhaysk. To return west by this route meant crossing 418 km of total desolation. Barren fields and burned buildings provided little sustenance or protection from the elements. But the southern route, through Kaluga, was relatively unspoiled. Napoléon could find food, forage, and shelter in plenty.

Sixty-eight-year-old Field Marshal Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov was a wily old fox. He led a formidable force. Many veterans had died in fighting to date. Their replacements were hastily trained new recruits. But the Russian soldier was famous for bravery, stubbornness, and fanatical devotion to their country. As far back as Frederick the Great, it was said it was easier to kill a Russian than to force him to retreat. This axiom had proved true many times in the Napoleonic Wars. They were eager for battle. They would not rest so long as one French soldier remained in Russia.

Kutuzov’s strategy was to let the elements and deprivation do the work. Where possible, he would strike hard and fast. But he preferred to avoid set-piece battles against the Grand Army. Kaluga was key to this strategy. It was as important for him to hold it as for Napoléon to take it. To this end, Kutuzov sent VI Corps to hold the bridge town of Maloyaroslavets. It was just south of the Luzha River. Behind it, the ground rose to a plateau overlooking it. There were two crossings, one just north of it and one east at Spassky. Retreating soldiers had destroyed the bridges.

VI Corps had 24,500 men: 12 Jäger and 24 Line Infantry battalions; 8 Russian cavalry squadrons; 4 Cossack companies; and 5 Foot Artillery Batteries. Each battery comprised eight 6-pound guns, so-called for their weight of shot, and four howitzers. VI Corps commander, 60-year-old General of Infantry Dmitry Sergeyevich Dokhturov, was stalwart on the defense. He stated, “Napoléon wants to break through. He will pass over my corpse!”

Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais’ IV Corps led Napoléon’s vanguard. At dusk, General of Division Alexis Joseph Delzons’s 13th Division, 16 battalions: 8th Light Infantry; 84th, 92nd, and 106th Line Infantry; 1st Croats, reached the Luzha, 23 October. He partially repaired the bridge. He entered Maloyaroslavets. He left two battalions to hold it. The rest guarded the crossings. At dawn, he would continue south. Dokhturov arrived at dawn, 24 October. He occupied the plateau.

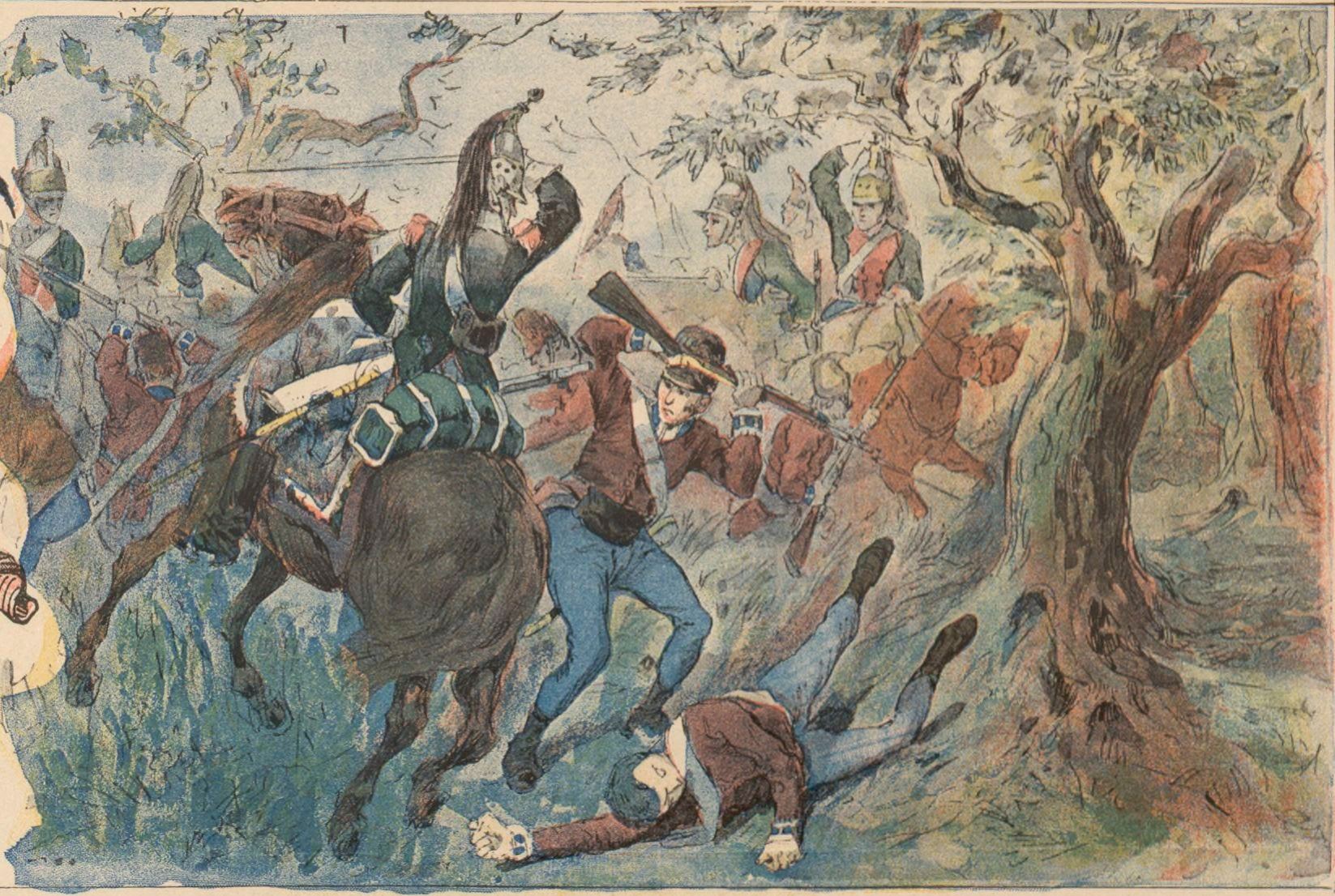

At 05:00, he sent the 6th and 33rd Jägers to seize Maloyaroslavets. Russians were famed for their savagery and skill with the bayonet. An old proverb went, “Bullet’s a moron, bayonet’s a fine chap.” The 33rd, 1,000 men, quickly entered the town. Their bayonets drove the French out, all the way to the river. The 6th and 11th Jägers reinforced them. General Major Aleksey Petrovich Yermolov took command. He was an expert rearguard commander.

Beauharnais heard the fighting. He rode to the front. Delzons explained the situation. Beauharnais ordered Delzons to lead his entire division over the Luzha. It was a terrible proposition. Kutuzov’s batteries on the plateau had a clear field of fire to the Luzha crossing and all the ground between it and the town. The same high ground protected the batteries from Beauharnais’ own guns. But it had to be done. At 11:00, Delzons led his men over.

A horrific fight developed. Yermolov’s inspired leadership and the Russian ferocity in close combat soon saw the 13th retreat. Delzons rushed forward to inspire them. He led bravely. A line of Russian infantry fired at him. He was hit three times, including in the head. He died. General of Brigade Armand Charles Guilleminot took over. At length, sheer numbers overpowered Yermolov. He retreated. Guilleminot knew Yermolov would return. He fortified the buildings with marksmen.

At 11:30, General of Division Jean-Baptiste Broussier’s 14th Division, 14 battalions: 18th Light Infantry; 9th, 35th, and 53rd Line Infantry; Joseph Bonaparte Infantry, entered Maloyaroslavets. They deployed on the highway from it to the plateau, 500 paces from Kutuzov’s batteries. A single salvo of canister shot sent them fleeing. Yermolov’s Jägers advanced again. The Liepaya and Sofia Infantry joined him. As a sign of contempt, they marched with unloaded muskets in silence.

The 6th Jägers entered Maloyaroslavets. Another violent fight began. Both sides took hideous casualties. Again, Russian bayonets and unrelenting battery fire sent the French fleeing to the bridge. Dokhturov sent the 19th and 40th Jägers hard on Yermolov’s heels. Guilleminot’s marksmen in the buildings remained at their posts. Fire from the buildings into the packed streets soon disordered the Russians. The French rallied and reentered the town.

Beauharnais refused to send his guns over the river. He worried he would lose them if he retreated. This put his men at a terrible disadvantage. At length, Yermolov drove the French to the town’s entrance. At 13:00, Beauharnais sent Milanese General of Division Domenico Pino’s 15th Italian Division, 16 battalions: 1st and 3rd Light Infantry; 2nd, 3rd, and Dalmatian Line Infantry. They had never fought before. They were eager. An eyewitness wrote:

“Pino’s division, which during the entire campaign was eager to fight, wanting to show its courage, seized on this case and enthusiastically obeyed the order of the prince.” They shouted “Long live the Emperor!” They charged. The city was now burning. Wounded men who fell were consumed by the flames. Italian artillery on the far bank traded shots with the Russians. Due to their poor ground, they had little effect. Russian fire devastated them.

At 14:00, General of Division Giuseppe Lecchi’s Italian Royal Guard Division moved up. The Guard Grenadiers, two battalions, and Chasseurs, one battalion, advanced. The Vilmanstrand Infantry joined Yermolov. Canister ripped into the Italians. But they pushed forward. There were now 15,000 French and Italians against 9,000 Russians. Yermolov was driven out of the town and uphill. The Italians crested the hill. They received a canister salvo at point-blank range. Survivors retreated into the town.

At 15:00, General Lieutenant Nikolay Nikolayevich Raevsky’s VII Corps arrived. General Major Illarion Illarionovich Vasilchikov’s 12th Division, 10 battalions: 41st Jägers; Aleksopol, Novo Ingermanlandiya, Narva, and Smolensk Infantry, advanced. They drove the exhausted French and Italians out. Maloyaroslavets was again Russian. Despite the defeat, it was said the Italians displayed “qualities which entitled them evermore to take rank among the bravest troops of Europe.”

Napoléon arrived with Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout’s I Corps and the Imperial Guard. Beauharnais’ messenger reported the situation. Napoléon replied, “Return to the viceroy and tell him that since he has begun to drink the cup, he must drain it. I have ordered Davout to support him.” General of Division Étienne Maurice Gérard’s 3rd, 15 battalions: 7th Light Infantry; 12th and 21st Line Infantry, and General of Division Jean Dominique Compans’ 5th, 15 battalions: 25th, 57th, and 111th Line Infantry, Divisions moved up. Maloyaroslavets changed hands again. Beauharnais finally sent his artillery over the Luzha.

Dokhturov and Raevsky retreated. They set up batteries. The carnage now reached a new intensity. The French advanced several times. Each time, Russian batteries flayed their columns with canister. They would retreat into town. The Russians would follow them in. They would be driven back again. Then the cycle would restart. Finally, Life Guard Artillery Colonel Petr Andrejevič Kozen deployed four horse guns at Maloyaroslavets’ entrance. They whipped canister down the streets, flaying the French. They were now confined to the town.

Kutuzov arrived late in the afternoon. He observed the action for a time. General Lieutenant Mikhail Mikhailovich Borozdin’s elite VIII Corps relieved Dokhturov and Raevsky. Its infantry consisted exclusively of grenadiers, large assault troops meant to clear breaches and break lines. General Major Prince Karl von Mecklenburg’s 2nd Grenadiers, 12 battalions: Astrakhan, Fanagoriya, Kiev, Malorossiya, Moskva, and Sibir Grenadiers, and General Major Mikhail Semënovič Voroncóv’s 2nd Combined Grenadiers, 10 battalions, advanced.

This time, the French held firm. Kutuzov turned to his friend, 3rd Division commander General Major Pyotr Petrovich Konovnitsyn. He said, “You know how much I care about you and always beg you not to throw yourself into the fire. But now I am asking you to clear this town out.” Konovnitsyn led two battalions of the combined grenadiers of the Chernigov, Kaporiye, Muromsk, and Revel Infantry down to Maloyaroslavets. He took command of the grenadiers already there.

The fighting was now pure animal savagery. Konovnitsyn led with exceptional coolness and bravery. But by dusk, he had to retreat. The French seized full control. They built strong batteries outside Maloyaroslavets. Their position was now secure. Fighting degraded into a long-range series of cannon and musket duels between the French and the Russians, 1 km away. But a new horror was about to begin.

Dokhturov sent two Jägers forward. They crept forward and laid a series of gunpowder charges in the town. Soon the town was an inferno. The French were brightly illuminated. They were easy targets. Russian batteries simply shelled wherever men gathered to extinguish the flames. Many wounded had taken refuge in the buildings. They now burned to death. By dawn, Maloyaroslavets was a burned-out ruin.

In 18 hours, Maloyaroslavets had changed hands eight times. The carnage was beyond belief. A Frenchman wrote, “The streets could be distinguished only by the numerous corpses with which they were strewn. At every step we came across severed arms and legs. Heads crushed by passing artillery pieces were lying around. All that remained of the houses were the smoking ruins, half-ruined skeletons under the burning ash.”

Kutuzov lost 19 officers, 45 non-commissioned officers, and 1,294 privates dead; 1 general, 136 officers, 153 NCOs, and 2,924 privates wounded; 31 NCOs and 2,248 privates missing. Most of the missing were probably dead and burned to ash. Napoléon lost 6,000 to 8,000 dead and wounded. He lost two generals and 88 officers dead, six generals and 241 officers wounded. Half the losses were Italian, including four generals and 152 officers. He lost 200 captives. Neither side bothered with prisoners.

Napoléon retreated to a house in Gorodnya. He summoned his marshals. He explained that the Russian army occupied the Kaluga Road in force. He then seemed to sink into a depression. He held his head in his hands. He gazed at his campaign map. He said nothing. His marshals had never seen him thus. After an hour, he dismissed them. He seemed to rally. He gave orders for another attack. But at 05:00, 25 October, he reconsidered.

He summoned Marshal Joachim Murat, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières, and his senior aide-de-camp, General of Division Georges Mouton. He asked them: “It appears the enemy will hold the positions they have occupied, and we shall have to give battle. Would this be to our advantage? Or would it not be better to avoid battle?” All three generals were unanimous. The Grand Army could not afford the losses it would take in a great battle. They had to retreat immediately. Napoléon decided to inspect the field one last time.

In the night, Kutuzov had released six Cossack regiments into Napoléon’s rear. Before dawn, they reached Gorodnya. They captured the Imperial Guard Artillery park. They carried off 11 guns and an eagle. Just then, Napoléon was riding south with three platoons of his Chasseurs à Cheval de la Garde Impériale. A platoon was scouting ahead. They crested a hill. They were horrified to see a swarm of Cossacks closing in. They informed Napoléon.

Napoléon turned and raced away. The three platoons and his personal retinue charged the Cossacks to buy time. Napoléon reached his main escort, three Guard squadrons. These charged the Cossacks. Soon the entire Guard cavalry arrived. The Cossacks rode off. Napoléon began carrying a bottle of poison around his neck, determined not to be taken alive. Other Cossacks rampaged in his rear, capturing five guns, hundreds of prisoners, and a convoy of stolen church silver. Also taken was a document containing Napoléon’s entire planned travel route along the Kaluga Road.

Napoléon reached Maloyaroslavets at 10:00. He remained until 17:00. He returned on 26 October. He seemed extraordinarily reluctant to abandon his plan. Kutuzov simply watched him. At 09:00, Napoléon ordered his men to turn around and retreat at speed to the devastated Mozhaysk Road. Ironically, Kutuzov was also preparing to retreat. He had decided he could not afford a great battle either. Thus, both commanders fled from each other, abandoning their designs on Kaluga.

By 27 October, the last French units left the vicinity of Maloyaroslavets. Napoléon would later say that, by forcing Kutuzov to retreat, he had saved his army’s honor. But he himself was fleeing. He had wasted a week’s worth of supplies and sapped the energies of his men just when they needed it the most. Kutuzov recovered quickly. He shadowed Napoléon, escorting him and keeping him off the Kaluga Road. The Cossacks and local partisans harried Napoléon mercilessly.

On the night of 27 October, the first frosts began to form. The dreaded Russian winter had begun.

(I owe a great debt to the scholar Peter Phillips, whose translations of primary source material have proven invaluable.)